Last updated on November 3, 2025

By Susan McWilliams

[Susan McWilliams presented the following remembrance of her father, (Wilson) Carey McWilliams, shortly after his passing. McWilliams had been a political science professor at Rutgers University, initially on the Livingston College faculty. He was posthumously honored in 2015 with the Livingston Legacy Award given by Livingston Alumni Association at Rutgers University. See his bio and award video.]

My father, Professor Wilson Carey McWilliams, died on March 29, [2005,] in his 35th year of teaching at Rutgers University.

My father, Professor Wilson Carey McWilliams, died on March 29, [2005,] in his 35th year of teaching at Rutgers University.

Dad loved Rutgers. He didn’t always love the campus or those responsible for it: He grumbled about the Hickman Hall elevators; he grumbled about those administrators who privilege football over financial aid; he grumbled about the increasingly elitist status of Rutgers College within the University system.

But he grumbled about these things because his love for Rutgers was a love for Rutgers’ student body. And her knew that those things, and others, made Rutgers a place that often burdened his students.

For my whole life, Dad would come home with stories about students: their hometowns, families, problems, and possibilities. He took evident joy in knowing them and learning from their lives.

So I was struck, at his funeral, not by how many students attended — I expected that, knowing how much he gave — but by how many introduced themselves with the caveat, “I was just a students of your father’s at Rutgers …”. This phrase, of course, implies that being a Rutgers students is an anonymous thing. These students had implied answered, negatively, this question: Should I, your professor’s daughter, care about you?

The thing was: Usually, I recognized these students’ names and remembered Dad’s stories about them. When I revealed that, they seemed surprised that my father had mentioned — or even known — them. I realize that my father was not the average professor. He was known, I am told, for his willingness to engage students, help them navigate the University bureaucracy, and give advice about problems one doesn’t often share with teachers.

But if there was one lesson Dad was committed to teaching at Rutgers — and he proved his commitment to teaching here, rejecting numerous offers from private schools, at greater salaries for fewer responsibilities — it was that his students should never feel nameless. My father, like Socrates, knew that there are no second-class souls.

My father was raised — a sick kid, with debilitating allergies and almost-fatal polio — by a working single mother in a time of few working single mothers. He went to a state university because he could afford it, and although he saw the temptations of fame and money, he knew that fame and money can’t teach anything that life — real life, unadorned by material surfaces — doesn’t teach better.

My father found particular joy in teaching at Rutgers because it is a public institution, which at its best stands against for forces of this privatist age. He loved the number of Rutgers students who are first-generation baccalaureates, who are immigrants, who attend this University to save parents money or worry, who are here just living an honest life. He always said he wanted to teach at Rutgers until he dropped dead; I am glad he did.

For my father, each of his students was a miracle — not just an independent miracle, but also a reflection of the human miracle. We are, as Jefferson said, created equally: made of the same stuff, born of the same bodily labors and subject to the same bodily end, who have the briefest opportunity to seek truth together by speaking truthfully.

Aristotle says in his Politics that humans are logistikon: beings who talk. What demarcates our species, even in light of what scientists learn, is our ability to communicate in terms particular and universal. We are aware of our partialness yet able to comprehend wholeness; we can speak about justice and abstract truth, and also speak about individual differences. We must recognize each other’s particularity in order to access what in us is universal, but we can never transcend our particularity — or imagine we should.

My father wished his students would learn from him that they are not properly defined as anonymous members of a fairly anonymous group — just Rutgers students — but defined by their fascinating particularities, and equally by their status as humans, seekers.

My father wished his students would learn from him that they are not properly defined as anonymous members of a fairly anonymous group — just Rutgers students — but defined by their fascinating particularities, and equally by their status as humans, seekers.

Dad knew that we humans are all kin. We are all worthy of remembering, and remembrance. My father remembered his students, and he hoped they would know him as someone who remembered them. He did, and so do I.

On behalf of Dad, I thank you, Rutgers students, for bringing to Wilson Carey McWilliams such joy and affirming his knowledge that we are best recognized through that love which acknowledges other people as equal partners in a mystery. As he said, we can only be cured — from all our problems, personal and political — by a better kind of love.

Susan McWilliams is an associate professor of politics at Pomona College in California.

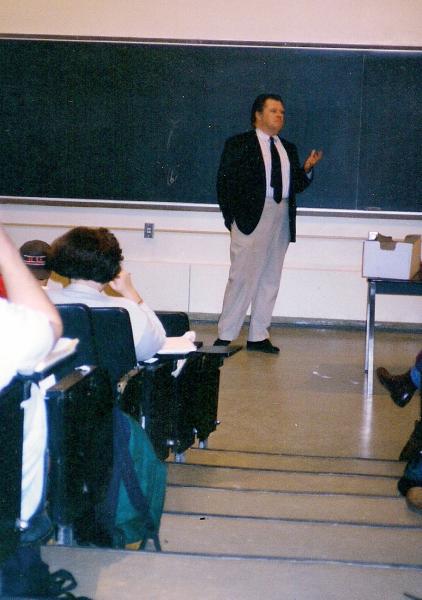

Photos: (Top) Carey McWilliams teaches a class at Lucy Stone Hall on Rutgers’ Livingston campus in October 1994. (Bottom) McWilliams plays with his daughters Helen and Susan in June 1982.